As of this writing, the 737 MAX remains grounded with projected return dates now stretching into the first quarter of 2020. Boeing has not as of yet submitted the software fix for the controversial MCAS system to the FAA for evaluation. The European Aviation Safety Agency (EASA) recently indicated that they will seek their own additional testing of the software fix possibly resulting in a staggered return of the aircraft to service.

The post-mortem examinations of what went wrong at Boeing and the assumptions that were made concerning the flawed MCAS software continue. At issue is one assumption made early on that any malfunction in the MCAS system would be immediately recognized by average pilots as a malfunction known as "runaway stabilizer" for which a checklist already exists.

The stabilizer trim system is used by the pilots or the autopilot to keep the horizontal stabilizer in "trim" which means keeping the stabilizer aligned with the slipstream of air. It does this by actually moving the entire stabilizer a through a range of angles which change with airspeed. An "out of trim" stabilizer means the stabilizer is not perfectly aligned with the passing wind. This results in the need to hold force on the control column to maintain altitude. Letting go of the controls in such a condition would result in an undesired climb or descent. A well trimmed aircraft will stay where you put it.

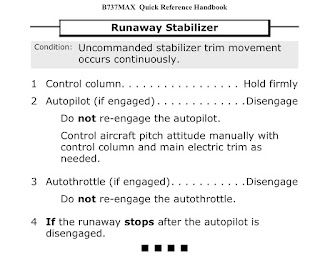

In the 737, the stabilizer trim is normally controlled electrically through a motor, but can also be adjusted manually through a wheel and handle on the center stand. This system has a failure mode known as "runaway trim" wherein the motor runs after the control column electric trim switch has been released most likely due to a sticky or failed switch. This malfunction can result in an unflyable condition if not quickly corrected. It is this failure mode which is addressed by the "runaway stabilizer" checklist reproduced above.

Continuously or Continually?

Boeing engineers were also counting on pilots using this same runaway stabilizer checklist in the event that the MCAS system, which also uses the stabilizer trim, malfunctioned. The problem with this assumption is that the two malfunctions can appear to be very different things. During a classic stuck switch runaway trim, the trim wheel in the cockpit starts spinning and does not stop. That's the definition of "continuously" and is correctly annotated as one of the conditions on the top of the checklist.

An MCAS malfunction, however, presented quite differently. During that malfunction, the MCAS system would spin the trim wheel forward for a specified amount and then stop. If the pilot then used the trim switches to adjust the trim in a nose up direction, a malfunctioning MCAS would wait five seconds and trim forward again after each input by the pilot. This "very often; at regular or frequent intervals" behavior of the MCAS system is the definition of "continually", not "continuously".

This is exactly what happened to Lion 610. After reversing the MCAS inputs multiple times, the captain passed control of the aircraft to his first officer who was apparently unaware of the inputs the captain had been making. He never countered the next MCAS input which doomed them.

From Dictionary [dot] com:

In formal contexts, continually should be used to mean “very often; at regular or frequent intervals,” and continuously to mean “unceasingly; constantly; without interruption.”

Is this a minor and pedantic point? Perhaps, but perhaps not. English is the international language of aviation, and all pilots are expected to be proficient in English to be qualified to fly in international airspace. The pilots of both Lion 610 and Ethiopian 302 were likely not native English speakers and were highly unlikely to be aware of such a nuance as the difference in meaning of these two words.

They were, however trained in the various failure modes of their aircraft, and were not likely to be expecting the intermittent behavior of the failed MCAS system. The pilots of Lion 610 had no knowledge of the existence of the MCAS system as it was not included in their flight manuals. The pilots of Ethiopian 302 did have the Emergency Airworthiness Directive (EAD) published by Boeing describing the MCAS system, but were still slow to recognize that their problem originated from a bad MCAS system until too late.

In Conclusion

Aircraft flight manuals should contain all the information needed by pilots to safely operate their aircraft. This information should include accurate descriptions of possible failures, the recognizance of such failures, and best practices on how to solve or mitigate problems that arise. The omission of the existence and description of MCAS from the MAX airplane flight manual only compounded the problems faced by the two mishap aircrews. Faced with a fusillade of warnings and distractions which served to conceal the real nature of their problem, they were defenseless against a poorly designed and undocumented but deadly adversary.

No comments:

Post a Comment

I welcome feedback. If you have any comments, questions or requests for future topics, please feel free to comment. Comment moderation is on to reduce spam, but I'll post all legit comments.Thanks for stopping by and don't forget to visit my Facebook page!

Capt Rob